Texas, USA

April 21, 2020

Plants are no strangers to diseases and devastating outbreaks. Humans can learn a valuable lesson from them when it comes to the current COVID-19 pandemic, according to a Texas A&M professor.

While the urge is to return to our workplace and business once diagnosed COVID-19 cases peak, a Texas A&M AgriLife Research virologist and plant pathologist says one must only turn to the plant world to see how that would be a mistake.

“When we reach the peak, we are at best only halfway towards coming down from this mountain of disease,” said Karen-Beth Scholthof, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology at Texas A&M University.

Scholthof concurs with Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, that social distancing should continue until there are essentially no new cases, no deaths.

Her reasoning is based on a long-standing concept from plant pathology, which she says describes the spread of any disease, explains why environmental measures matter, and sheds light on the similarities between plant and human diseases.

“All biology is connected. Now is the time to learn from other areas of science and the environment,” said Patrick J. Stover, vice chancellor of Texas A&M AgriLife, dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and director of AgriLife Research. “We may need to take extra time now, which we know will be difficult in the short-term, but life-saving for many in the long-term.

“The novel coronavirus is certainly revealing our vulnerabilities, from the food supply system to our social environments to the quality of life. We must learn from this experience, including prioritizing the development of cutting-edge technologies to protect from and prevent against COVID-19 and its far-reaching effects on our lives before we restart the vicious cycle once again, especially the most vulnerable.”

The disease triangle

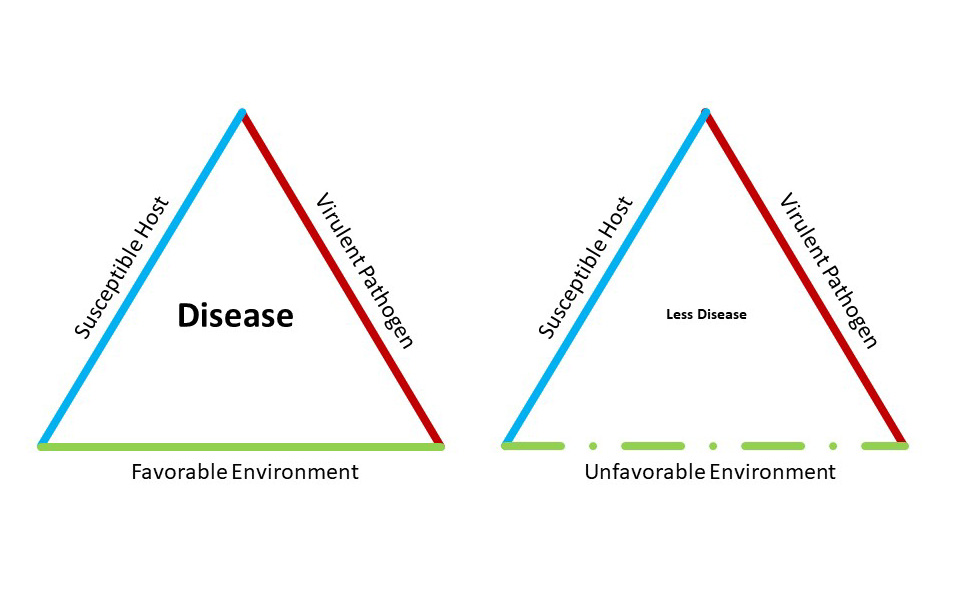

Disease outbreaks depend on the “disease triangle,” Scholthof said. This concept arose more than 60 years ago when George McNew, a plant pathologist at the Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research, diagrammed the fact that an epidemic arises from the interaction of three factors – a susceptible host, a virulent pathogen and a hospitable environment.

Scholthof said a simple form of McNew’s disease triangle is helpful to explain the key role of environment in the success of pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Genetically identical plants are a “monoculture” and are especially vulnerable to emerging pathogens and disease. Today, plant pathologists break these cycles of disease by modifying or controlling either the host, the pathogen or the environment.

“We may breed crops that are resistant to the disease, plant them in a different way or at different times or use chemical treatments to protect the plants from harmful fungi, viruses, bacteria and insects,” Scholthof explained. “By changing the host with resistance genes, stopping the pathogen with chemicals, or altering the environment by planting earlier or later, for example, we can control an outbreak of a new disease or seasonal recurrence of a known pathogen.”

In the case of COVID-19, people are the susceptible hosts and SARS-COV-2, the virulent pathogen. The constant and close contact between people is the hospitable environment needed to keep this pandemic going strong. The novel coronavirus, having jumped from an animal host, has become extraordinarily successful at infecting humans.

“We do not have population-wide immunity to this virus,” Scholthof said. “Again, from Dr. Fauci, we ‘don’t make the timeline, the virus makes the timeline.’ Until drugs or vaccines are shown to control the virus and the disease, we can only do our part to disrupt an environment that is favorable to the novel coronavirus.”

Taking a page out of plant pathology history

She used the Great Irish Potato Famine, a humanitarian crisis, to shed light on the close link between pathogens, the environment and society — including how an epidemic drives policy while unmasking social and economic injustice.

“These are issues that strike close to home since COVID-19 has become our daily reality,” Scholthof said.

The Irish potato famine was precipitated by late blight disease of potato, which still occurs today. First-hand reports from Ireland described how the blight sprung up overnight with fields of lush green plants suddenly destroyed, resulting the near total collapse of the potato crop.

Although disease outbreaks were also occurring in Europe and North America, the dependence of the Irish poor on the potato for most of their food calories was devastating. This plant disease outbreak led to the emigration of a million people from Ireland and another million deaths — a loss of 25% of the country’s population.

“It was a single pathogen that provided a horrifying lesson for the need to scientifically manage, reduce and control disease,” Scholthof said. “COVID-19 will recur if we do not continue to perturb the virus’s favored environment until either a vaccine to strengthen the host or medications to destroy the virus are created.”

Controlling the outbreak

There may be a single peak of infection, waves of infection, or seasonal recurrence of COVID-19 in our communities, Scholthof said. Similarly, potato late blight disease that caused such destruction is ongoing today, but in a controlled environment.

“Ongoing COVID-19 infections would suggest that we have not been sufficiently vigilant with perturbing the virus’s favored environment,” she said. “Today, and for at least the near future, disrupting a favorable environment for the virus is the main element of controlling the spread of the disease, and the disruption must continue until either proven vaccines or medications are created.”

Social distancing and good hygienic practices remain the best community options available to break the disease triangle, Scholthof said. Simple efforts such as handwashing disrupt the virus’s membrane envelope, preventing it from initiating an infection.

“With time, we, the host, may acquire ‘herd immunity’ as a form of protection from the virus,” she said. “Or the amazing ongoing scientific work may identify safe and effective treatments or a vaccine.

“But we must remain vigilant in continuing with the recommended practices that create an unfavorable environment for the virus until that time occurs,” Scholthof said. “We must not become complacent.”