Gainesville, Florida, USA

July 18, 2022

If you savor a juicy watermelon in the scorching summer heat, Florida farmers toil to meet your tastes. The Sunshine State leads the nation in watermelon production.

But, like all farmers, those who produce watermelons seek ways to control diseases, so they don’t lose all or part of their crops. The needs of growers drive Yiannis Ampatzidis to use artificial intelligence to detect pathogens early and accurately.

One such disease, downy mildew, spreads like wildfire, said Ampatzidis, a UF/IFAS associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering.

For a new study, Ampatzidis used AI to help find downy mildew.

In newly published research, Ampatzidis used spectral reflectance — the energy a surface reflects at specific wavelengths — of plant canopies and machine learning to quickly and efficiently detect downy mildew in several stages of the disease.

Hopefully, farmers can take advantage of this technology.

]

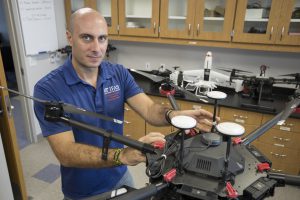

Yiannis Ampatzidis, a UF/IFAS agricultural engineer at the Southwest Florida Research and Education Center, is shown with drones in the laboratory. UF/IFAS photograhy.

“If left unchecked, downy mildew can destroy a farmer’s entire crop within days. That’s why it gets the nickname ‘wildfire.’ It spreads rapidly and scorches leaves,” said Ampatzidis, a faculty member at the Southwest Florida Research and Education Center.

Ampatzidis and his research team successfully detected downy mildew in several stages of severity.

“Our most important result was finding downy mildew in its earliest stage, which is critical to growers’ ability to manage this disease,” he said.

Ampatzidis and his research team developed two methods, utilizing hyperspectral imaging and AI — one in the laboratory and the other using UAVs (drones) for field detection.

Downy mildew does not affect stems or fruit directly. But it can defoliate the plants, leaving fruit exposed to sun damage, making it unmarketable. That’s critical because, as of 2019, Florida farmers harvested watermelon from 24,500 acres in Florida, with a packinghouse value of $161 million.

As long as consumers continue to buy watermelon — and those who grow the fruit want to reap a good harvest — Ampatzidis will continue to find ways to find pathogens that could damage the fruit.

As next steps in his research, Ampatzidis wants to develop a simple and inexpensive drone-based sensor to improve detection of downy mildew in watermelon plants.