Fayetteville, Arkansas, USA

January 20, 2017

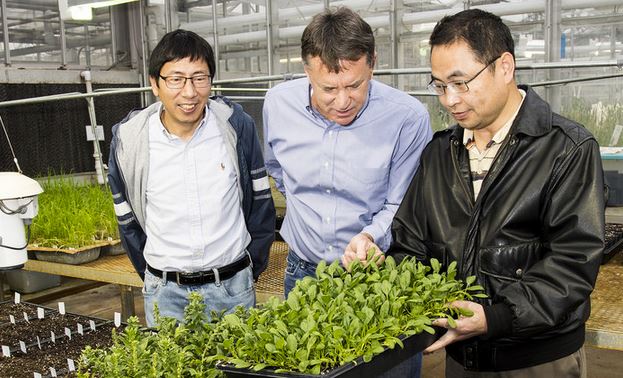

Research associate Dr. Chunda Feng, right, shows spinach plants in a disease resistance study to project leaders Dr. Ainong Shi, left, and Dr. Jim Correll.

From a plant scientist’s point of view, farmers are locked in a biological arms race with nature.

For spinach, the greatest threat comes from a disease called downy mildew, caused by the pathogen Peronospora effusa.

“The U.S. is the second largest producer of spinach,” said Ainong Shi, a University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture vegetable breeder. “And there has been a dramatic increase in spinach production as a result of higher consumption.

“The most yield-limiting disease in spinach in the U.S. is downy mildew,” Shi said. “In order to keep up with demand, growers require continuous development of improved and adapted spinach varieties to overcome diseases and insect pests.”

Remember that arms race?

James Correll, a Division of Agriculture plant pathologist, said the first, best line of defense against plant diseases is resistance. Plant breeders continually develop crop varieties that have improved disease resistance. But new races of the pathogens emerge and eventually find ways to overcome the resistance.

So, plant breeders develop a new crop variety with improved resistance, and the race continues.

Shi and Correll have teamed up to bring new tools to the arena. They are mounting a three-year research program funded by a $725,552 USDA Specialty Crop Multistate Program grant administered through the Arkansas Agriculture Department.

They are also teaming up with Beiquan Mou, a research geneticist in the USDA Crop Improvement and Protection Unit in Salinas, Calif.

Correll’s team brings decades of research on downy mildew to the partnership. They have had numerous USDA grants to examine how this pathogen attacks spinach throughout the world.

Shi brings a host of genetic tools and knowledge to the table.

“We are developing new strategies for breeding spinach varieties with durable resistance to ensure long-term disease control,” Shi said.

Shi’s strategy is three-pronged. First, he is identifying quantitative gene loci — the locations of particular genes in DNA — that control disease resistance.

Marker-assisted Selection uses genetic markers to identify disease resistant breeding lines, Shi said, and to determine if resistance has been transferred by conventional crossbreeding.

And breeding efforts will focus on gene pyramiding, or gene stacking, Shi said. By this strategy, multiple genes for resistance to downy mildew will be bred into improved spinach varieties. The result would be plants with multiple means of defense against the disease-causing pathogen.

Shi said the goal of the collaborative research is to use these advanced genetic tools to more efficiently develop improved spinach varieties through conventional breeding methods.