Germany

December 10, 2021

Some plants master a special form of solar energy utilization that offers great advantages under warm conditions. A recent study now provides new insights into an enzyme that plays a central role in this so-called C4 photosynthesis. The work, led by the University of Bonn, also involved researchers from Argentina, Canada and the University of Düsseldorf. It has been published in the journal The Plant Cell.

The plant, - in which the structure of the C4-NAD malate enzyme was elucidated, may be familiar to some people in Germany as an ornamental plant. © Photo: Meike Hüdig/University of Bonn

The plant, - in which the structure of the C4-NAD malate enzyme was elucidated, may be familiar to some people in Germany as an ornamental plant. © Photo: Meike Hüdig/University of Bonn

During photosynthesis, plants use sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into carbohydrates and oxygen. They take up the carbon dioxide from the ambient air through stomata on the surface of their leaves. At very warm temperatures, however, these close to prevent excessive water loss.

Around three percent of all plants have therefore developed a trick that enables them to use even the smallest amounts of CO2: C4 photosynthesis. In this process, they first pre-fix the carbon dioxide by linking it to a transport molecule. This step works even at very low CO2 concentrations; the plant therefore only has to open its stomata briefly. This pre-fixation takes place in the mesophyll, the cells inside the leaf that are adjacent to the ambient air. They surround the bundle sheath cells, which are not in direct contact with the air.

Chemical pre-fixation produces an organic compound containing four carbons - hence the name C4 photosynthesis. This is transported into the bundle sheath cells, which are specially sealed. Here, the carbon dioxide is released again and is then available for the further reactions of photosynthesis. "This release step is catalyzed by a special enzyme," explains Prof. Dr. Veronica Maurino of the Molecular Plant Physiology Department at the University of Bonn, who led the study. "Some of the plants use the so-called NAD-malate enzyme for this purpose."

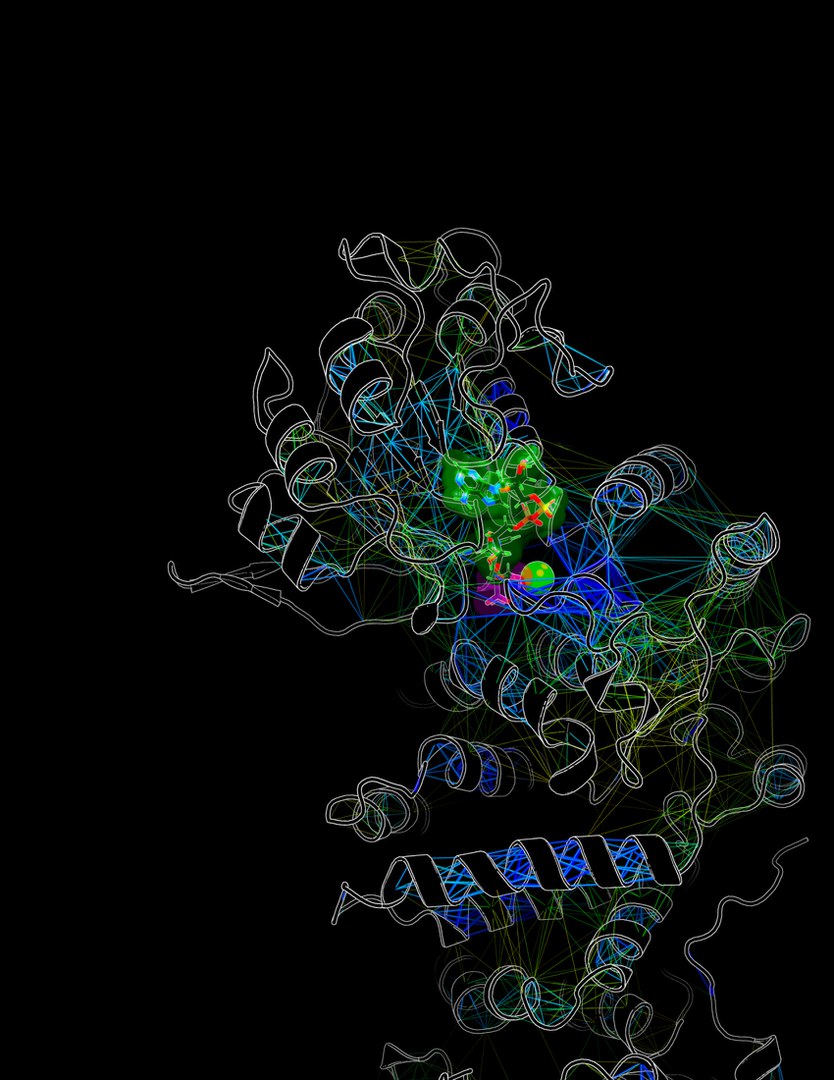

Model - of the C4-NAD-malate enzyme from the genus Cleome, which has now been analyzed for the first time. © Image: David Bickel/Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf

Model - of the C4-NAD-malate enzyme from the genus Cleome, which has now been analyzed for the first time. © Image: David Bickel/Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf

Similar enzymes, different tasks

Until now, it was unclear exactly how C4-NAD-ME (as it is abbreviated), which is involved in C4 photosynthesis, is structured and functions. The partners from Germany, Canada and Argentina have now investigated this using an ornamental plant of the genus Cleome as an example. According to the study, NAD-ME consists of two large building blocks, the alpha and the beta subunit. While the alpha unit is responsible for CO2 release, the beta subunit serves primarily to regulate the activity of the enzyme.

And it is precisely this regulation that is probably extremely important. This is because the release of carbon dioxide takes place in the "power engines" of the cells, the mitochondria, where important metabolic processes are constantly taking place. Some of these are also catalyzed by NAD-ME, but by a completely different variant. "This one is much slower in terms of reaction speed than the C4-NAD-ME used in C4 photosynthesis," emphasizes Prof. Maurino.

The beta subunit apparently prevents the two enzymes from getting in each other's way. This is because it regulates the reaction rate of C4-NAD-ME. To do this, it binds an intermediate product of the C4 photosynthesis cycle called aspartate. And this aspartate ensures that the "photosynthetic variant" of NAD-ME becomes particularly active. The CO2 that is pre-fixed and intended for photosynthesis is thus mainly processed by the enzyme variant that "matches" it (and works much faster).

Beta subunit has changed a lot in the course of evolution

Incidentally, the photosynthetic version of NAD-ME evolved from the slow variant responsible for general NAD-ME tasks in the plant mitochondrion. "Both the alpha and beta subunit genes duplicated at some point during evolution," Maurino explains. "The second version of the alpha gene was then lost again, and the remaining single gene changed little after that. One of the duplicated beta copies, on the other hand, mutated at many different sites. It thus lost its original function and instead acquired the ability to regulate the activity of the new enzyme."

This complex evolution may also be the reason why the release of the pre-fixed carbon dioxide works differently in most C4 plants than in the genus Cleome. One example is maize: the sweet grass, which originated in Mexico where it had to evolve the ability to photosynthesize without losing too much water, has an enzyme other than NAD-ME to do so. "Our results help us better understand the evolution of the different groups of C4 plants," the scientist says. "It could also help transfer the C4 mechanism to crops that haven't mastered this efficient form of photosynthesis."

Funding:

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Canadian Natural Science and Engineering Research Council.

Publication: Meike Hüdig, Marcos A. Tronconi, Juan P. Zubimendi, Tammy L. Sage, Gereon Poschmann, David Bickel, Holger Gohlke and Veronica G. Maurino: Respiratory and C4-photosynthetic NAD-malic enzyme coexist in bundle sheath cell mitochondria and evolved via association of differentially adapted subunits; The Plant Cell; http://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koab265

Schlüsselmechanismus der Photosynthese aufgeklärt

Studie unter Federführung der Uni Bonn liefert neue Einblicke in die Evolution dieses wichtigen Prozesses

Einige Pflanzen beherrschen eine Sonderform der Sonnenenergie-Nutzung, die unter warmen Bedingungen große Vorteile bietet. Eine aktuelle Studie liefert nun neue Erkenntnisse zu einem Enzym, das bei dieser sogenannten C4-Photosynthese eine zentrale Rolle spielt. An der Arbeit unter Federführung der Universität Bonn waren auch Forschende aus Argentinien, Kanada und der Universität Düsseldorf beteiligt. Sie ist in der Zeitschrift The Plant Cell erschienen.

Bei der Photosynthese wandeln Pflanzen mit Hilfe des Sonnenlichts Kohlendioxid und Wasser zu Kohlenhydraten und Sauerstoff um. Das Kohlendioxid entnehmen sie dabei der Umgebungsluft, und zwar durch die Spaltöffnungen (Stomata) auf der Oberfläche ihrer Blätter. Bei sehr warmen Temperaturen schließen sich diese aber, um zu große Wasserverluste zu vermeiden.

Rund drei Prozent aller Pflanzen haben daher einen Trick entwickelt, mit dem sie auch noch geringste CO2-Mengen nutzen können: die C4-Photosynthese. Dabei fixieren sie das Kohlendioxid zunächst einmal vor, indem sie es an ein Transportmolekül koppeln. Dieser Schritt funktioniert auch noch bei sehr kleinen CO2-Konzentrationen; die Pflanze muss ihre Stomata also nur kurz öffnen. Die Vorfixierung findet im Mesophyll statt, den Zellen, die im Blattinneren an die Umgebungsluft angrenzen. Sie umschießen die Bündelscheidezellen, die nicht in direktem Kontakt mit der Luft stehen.

Bei der chemischen Vorfixierung entsteht eine organische Verbindung mit vier Kohlestoffen - daher der Name C4-Photosynthese. Diese wird in die Bündelscheidezellen transportiert, die speziell abgedichtet sind. Hier wird das Kohlendioxid wieder freigesetzt und steht dann für die weiteren Reaktionen der Photosynthese zur Verfügung. „Dieser Abspaltungs-Schritt wird durch ein spezielles Enzym katalysiert“, erklärt Prof. Dr. Veronica Maurino von der Molekularen Pflanzenphysiologie der Universität Bonn, die die Studie geleitet hat. „Ein Teil der Pflanzen nutzt dazu das sogenannte NAD-Malatenzym.“

Ähnliche Enzyme, unterschiedliche Aufgaben

Bislang war unklar, wie das C4-NAD-ME (so die Abkürzung), das an der C4 Photosynthese beteiligt ist, genau aufgebaut ist und funktioniert. Die Partner aus Deutschland, Kanada und Argentinien haben das nun exemplarisch für eine Zierpflanze der Gattung Cleome untersucht. Demnach besteht NAD-ME aus zwei großen Bausteinen, der Alpha- und der Beta-Untereinheit. Während die Alpha-Einheit für die CO2-Abspaltung zuständig ist, dient die Beta-Untereinheit vor allem dazu, die Aktivität des Enzyms zu regulieren.

Und gerade diese Regulation ist wohl ausgesprochen wichtig. Denn die Freisetzung des Kohlendioxids erfolgt in den „Kraftwerken“ der Zellen, den Mitochondrien, wo ständig wichtige Stoffwechselprozesse stattfinden. Einige davon werden ebenfalls durch NAD-ME katalysiert, aber von einer ganz anderen Variante. „Diese ist hinsichtlich ihrer Reaktionsgeschwindigkeit weitaus langsamer als das C4-NAD-ME, das bei der C4-Photosynthese genutzt wird“, betont Prof. Maurino.

Die Beta-Untereinheit verhindert augenscheinlich, dass sich beide Enzyme in die Quere kommen. Denn sie reguliert die Reaktionsgeschwindigkeit des C4-NAD-ME. Dazu bindet sie ein Zwischenprodukt des C4-Photosynthese-Kreislaufs namens Aspartat. Und dieses Aspartat sorgt dafür, dass die „Photosynthese-Variante“ des NAD-ME besonders aktiv wird. Das vorfixierte und für die Photosynthese gedachte CO2 wird also hauptsächlich von der zu ihm „passenden“ (und viel schneller arbeitenden) Enzym-Variante verarbeitet.

Beta-Untereinheit hat sich im Laufe der Evolution stark verändert

Die Photosynthese-Version des NAD-ME ist übrigens aus der langsamen Variante entstanden, die für die allgemeinen NAD-ME Aufgaben im Mitochondrium der Pflanze zuständig ist. „Sowohl das Gen für die Alpha- als auch das für die Beta-Untereinheit haben sich irgendwann im Laufe der Evolution verdoppelt“, erklärt Maurino. „Die zweite Version des Alpha-Gens ging dann wieder verloren, und das verbleibende einzelne Gen hat sich danach kaum verändert. Eine der verdoppelte Beta-Kopien ist dagegen an vielen verschiedenen Stellen mutiert. Sie hat dadurch ihre ursprüngliche Funktion verloren und stattdessen die Fähigkeit erworben, die Aktivität des neuen Enzyms zu regulieren.“

Diese komplexe Evolution ist wohl auch möglicherweise der Grund, warum die Abspaltung des vorfixierten Kohlendioxids bei den meisten C4-Pflanzen anders funktioniert als bei der Gattung Cleome. Ein Beispiel ist der Mais: Das Süßgras, das ursprünglich aus Mexiko stammt und dort die Fähigkeit entwickeln musste, ohne allzu großen Flüssigkeitsverlust Photosynthese zu treiben, verfügt dazu über ein anderes Enzym als NAD-ME. „Unsere Ergebnisse helfen uns, die Evolution der verschiedenen Gruppen von C4-Pflanzen besser zu verstehen“, sagt die Wissenschaftlerin. „Außerdem könnte sie dabei helfen, den C4-Mechanismus auf Nutzpflanzen zu übertragen, die diese effiziente Form der Photosynthese nicht beherrschen.“

Förderung:

Die Studie wurde durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) und das Kanadische Natural Science and Engineering Research Council gefördert.

Publikation: Meike Hüdig, Marcos A. Tronconi, Juan P. Zubimendi, Tammy L. Sage, Gereon Poschmann, David Bickel, Holger Gohlke und Veronica G. Maurino: Respiratory and C4-photosynthetic NAD-malic enzyme coexist in bundle sheath cell mitochondria and evolved via association of differentially adapted subunits; The Plant Cell; http://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koab265