Würzburg, Germany

February 16, 2021

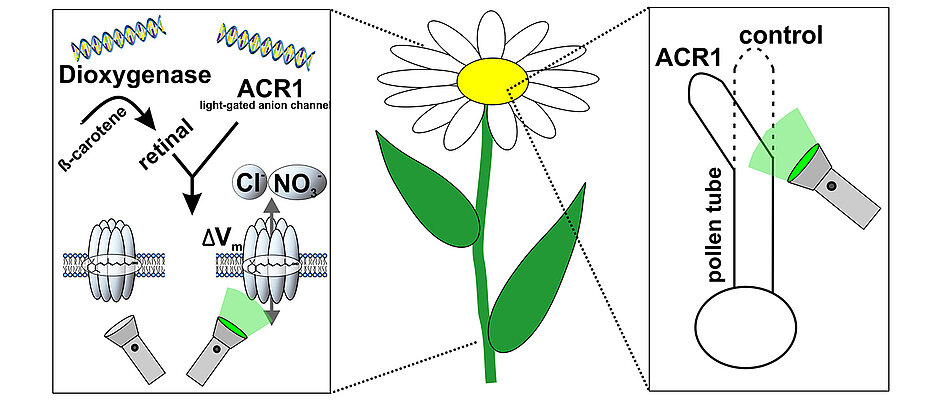

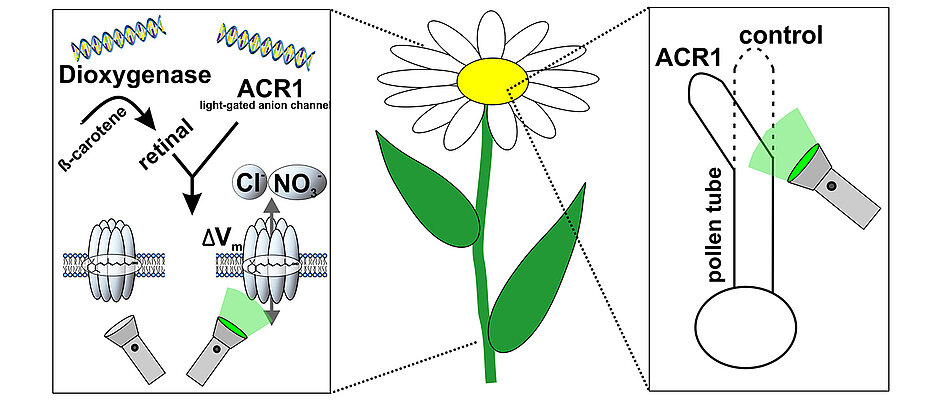

With two additional genes for the enzyme dioxygenase and the light-controlled anion channel ACR1, the tobacco plant can channel salt ions across the cell membrane when exposed to green light. The success can be seen in the experiment: While pollen tubes normally grow in the direction of the egg cell for fertilization, in genetically modified cells they change the direction of growth depending on the exposure to light. (Image: Dr. Kai Konrad)

With two additional genes for the enzyme dioxygenase and the light-controlled anion channel ACR1, the tobacco plant can channel salt ions across the cell membrane when exposed to green light. The success can be seen in the experiment: While pollen tubes normally grow in the direction of the egg cell for fertilization, in genetically modified cells they change the direction of growth depending on the exposure to light. (Image: Dr. Kai Konrad)

It is almost ten years since the scientific journal Science called optogenetics the "breakthrough of the decade". Put simply, the technique makes it possible to control the electrical activity of cells with pulses of light. With its help, scientists can gain new insights into the functioning of nerve cells, for example, and thus better understand neurological and psychiatric diseases such as depression and schizophrenia.

Established procedure on animal cells

In research on animal cells, optogenetics is now an established technique used in many fields. The picture is different in plant research: transferring the principle to plant cells and applying it widely has not been possible until now.

However, this has now changed: Scientists at the Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg (JMU) have succeeded in applying optogenetic methods in tobacco plants. They present the results of their work in the current issue of the journal Nature Plants. "In particular, Dr. Kai Konrad from Prof. Hedrich's group (Botany I) and Dr. Shiqiang Gao from my group were mainly responsible for the success of this project" explains Professor Georg Nagel, co-founder of optogenetics. In addition to the Department of Neurophysiology in the Institute of Physiology, three chairs of the Julius-von-Sachs Institute were involved in the collaboration: Botany I, Botany II and Pharmaceutical Biology.

Light switch for cell activity

"Optogenetics is the manipulation of cells or living organisms by light after a 'light sensor' has been introduced into them using genetic engineering methods. In particular, the light-controlled cation channel channelrhodopsin-2 has helped optogenetics achieve a breakthrough," says Nagel, describing the method he co-developed. With the help of channelrhodopsin, the activity of cells can be switched on and off as if with a light switch.

In plant cells, however, this has so far only worked to a limited extent. There are two main reasons for this: "It is difficult to genetically modify plants so that they functionally produce rhodopsins. In addition, they lack a crucial cofactor without which rhodopsins cannot function: all-trans retinal, also known as vitamin A," explains Dr. Gao.

Green light for plant cells

Prof. Nagel, Dr. Gao, Dr. Konrad, and colleagues have now been able to solve both problems. They have succeeded in producing vitamin A in tobacco plants by means of an introduced enzyme from a marine bacterium, thus enabling improved incorporation of rhodopsin into the cell membrane. This allows, for the first time, non-invasive manipulation of intact plants or selected cells by light via the so-called anion channel rhodopsin GtACR1.

In an earlier approach, plant physiologists from Botany I had artificially added the much-needed cofactor vitamin A to cells to allow a light-gated cation channel to become active in plant cells (Reyer et al., 2020, PNAS). Using the genetic trick now presented, Prof. Nagel and colleagues have generated plants that produce a special enzyme in addition to a rhodopsin, called dioxygenase. These plants are then able to produce vitamin A - which is normally not present in plants - from provitamin A which is abundant in the plant chloroplast. The combination of vitamin A production and optimization of rhodopsins for plant application ultimately led the researchers led by Prof. Nagel, Dr. Konrad and Dr. Gao to success.

New approach for plant research

"If you irradiate these cells with green light, the permeability of the cell membrane for negatively charged particles increases sharply, and the membrane potential changes significantly," explains Dr. Konrad. In this way, he says, it is possible to specifically manipulate the growth of pollen tubes and the development of leaves, for example, and thus to study the molecular mechanisms of plant growth processes in detail. The Würzburg researchers are confident that this novel optogenetic approach to plant research will greatly facilitate the analysis of previously misunderstood signaling pathways in the future.

A pioneer of optogenetics

Rhodopsin is a naturally light-sensitive pigment that forms the basis of vision in many living organisms. The fact that a light-sensitive ion pump from archaebacteria (bacteriorhodopsin) can be incorporated into vertebrate cells and function there was first demonstrated by Georg Nagel in 1995 together with Ernst Bamberg at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysics in Frankfurt. In 2002/2003, this proof was then also achieved with light-sensitive ion channels from algae.

Together with Peter Hegemann, Nagel demonstrated the existence of two light-sensitive channel proteins, channelrhodopsin-1 and channelrhodopsin- 2 (ChR1/ChR2), in two papers published in 2002 and 2003. Crucially, the researchers discovered that ChR2 elicits an extremely rapid, light-induced change in membrane current and membrane voltage when the gene is expressed in vertebrate cells. In addition, ChR2's small size makes it very easy to use.

Nagel has since then received numerous awards for this discovery, most recently in 2020 - together with two other pioneers of optogenetics - the $1.2 million Shaw Prize for Life Sciences.

Original publication

"Optogenetic control of plant growth by a microbial rhodopsin," Yang Zhou, Meiqi Ding, Shiqiang Gao, Jing Yu-Strzelczyk, Markus Krischke, Xiaodong Duan, Jana Leide, Markus Riederer, Martin J. Mueller, Rainer Hedrich, Kai R. Konrad, Georg Nagel. Nature Plants. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-021-00860-x

Ein Schub für die Pflanzenforschung

Mit Hilfe der Optogenetik lassen sich Zellen gezielt mit Licht aktivieren und erforschen. Wissenschaftlern der Universität Würzburg ist es jetzt gelungen, diese Technik auf Pflanzen zu übertragen

Mit zwei zusätzlichen Genen für das Enzym Dioxygenase und den Licht-gesteuerten Anionenkanal ACR1 kann die Tabakpflanze bei Belichtung mit grünem Licht Salzionen über die Zellmembran schleusen. Der Erfolg zeigt sich im Experiment: Während Pollenschläuche normalerweise zur Befruchtung in Richtung Eizelle wachsen, verändern sie bei genetisch veränderten Zellen die Wachstumsrichtung je nach Belichtung. (Bild: Dr. Kai Konrad)

Mit zwei zusätzlichen Genen für das Enzym Dioxygenase und den Licht-gesteuerten Anionenkanal ACR1 kann die Tabakpflanze bei Belichtung mit grünem Licht Salzionen über die Zellmembran schleusen. Der Erfolg zeigt sich im Experiment: Während Pollenschläuche normalerweise zur Befruchtung in Richtung Eizelle wachsen, verändern sie bei genetisch veränderten Zellen die Wachstumsrichtung je nach Belichtung. (Bild: Dr. Kai Konrad)

Knapp zehn Jahre ist es her, dass das Wissenschaftsmagazin Science die Optogenetik als „Durchbruch des Jahrzehnts“ bezeichnet hat. Die Technik ermöglicht es, vereinfacht gesagt, die elektrische Aktivität von Zellen mit Lichtpulsen zu steuern. Mit ihrer Hilfe können Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftler beispielsweise neue Einblicke in die Funktionsweise von Nervenzellen gewinnen und damit neurologische und psychiatrische Krankheiten, wie etwa Depression und Schizophrenie, besser verstehen.

Etabliertes Verfahren an tierischen Zellen

In der Forschung an tierischen Zellen ist die Optogenetik inzwischen eine etablierte Technik, die in vielen Bereichen zum Einsatz kommt. Anders das Bild in der Pflanzenforschung: Die Übertragung des Prinzips auf Pflanzenzellen und dessen breite Anwendung war bislang nicht möglich.

Das allerdings hat sich jetzt geändert: Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftlern der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU) ist es gelungen, optogenetische Verfahren in Tabakpflanzen anzuwenden. Die Ergebnisse ihrer Arbeit stellen sie in der aktuellen Ausgabe der Fachzeitschrift Nature Plants vor.

„Insbesondere Dr. Kai Konrad aus der Arbeitsgruppe von Professor Rainer Hedrich (Botanik I) und Dr. Shiqiang Gao aus meiner Gruppe waren hierbei für den Erfolg dieses Projekts hauptverantwortlich“, erklärt Professor Georg Nagel, Mitbegründer der Optogenetik. An der Zusammenarbeit waren – neben der Abteilung Neurophysiologie im Physiologischen Institut – drei Lehrstühle des Julius-von-Sachs-Instituts der JMU beteiligt: die Botanik I, Botanik II und die Pharmazeutische Biologie.

Lichtschalter für die Zellaktivität

„Unter Optogenetik versteht man die Manipulation von Zellen oder Lebewesen durch Licht, nachdem mit gentechnischen Verfahren ein ‚Lichtsensor‘ in diese eingebracht wurde. Insbesondere der lichtgesteuerte Kationenkanal Channelrhodopsin-2 hat der Optogenetik zu einem Durchbruch verholfen“, beschreibt Nagel das von ihm mitentwickelte Verfahren. Mit Hilfe des Channelrhodopsins kann die Aktivität von Zellen quasi wie mit einem Lichtschalter an- und ausgeknipst werden.

In Pflanzenzellen hat dies bislang allerdings nur eingeschränkt geklappt. Verantwortlich dafür waren vor allem zwei Gründe: „Es ist schwer, Pflanzen genetisch so zu verändern, dass sie Rhodopsine funktionell bilden. Darüber hinaus fehlt ihnen ein entscheidender Ko-Faktor, ohne das Rhodopsine nicht funktionieren können: das all-trans-Retinal, auch Vitamin A genannt“, erklärt Dr. Gao.

Grünes Licht für Pflanzenzellen

Beide Probleme konnten Professor Nagel, Dr. Gao und Dr. Konrad und Kollegen jetzt lösen. Ihnen ist es gelungen, Vitamin-A in Tabakpflanzen mittels eines eingebrachten Enzyms aus einem marinen Bakterium zu produzieren und damit einen verbesserten Einbau von Rhodopsin in die Zellmembran zu ermöglichen. Dies erlaubt erstmals eine nicht-invasive Manipulation von intakten Pflanzen oder ausgewählten Zellen durch Licht über das sogenannte Anionenkanalrhodopsin GtACR1.

In einem früheren Ansatz hatten die Pflanzenphysiologen aus der Botanik I den dringend notwendigen Ko-Faktor Vitamin A den Zellen künstlich zugefügt, um einen lichtgesteuerten Kationenkanal in Pflanzenzellen aktiv werden zu lassen. Mit Hilfe des jetzt vorgestellten genetischen Tricks haben Nagel und seine Kollegen nun Pflanzen erzeugt, die neben einem Rhodopsin ein spezielles Enzym produzieren – die sogenannte Dioxygenase – und damit in der Lage sind, aus dem Provitamin A das in der Pflanze nicht vorkommende Vitamin A selbst herzustellen. Die Kombination von Vitamin-A-Produktion und Optimierung von Rhodopsinen für die pflanzliche Anwendung führte die Forscher letztendlich zum Erfolg.

Neuer Ansatz für die Pflanzenforschung

„Bestrahlt man diese Zellen mit Grünlicht, steigt die Durchlässigkeit der Zellmembran für negativ geladene Teilchen stark an, und das Membranpotenzial verändert sich deutlich“, erklärt Dr. Konrad. Auf diese Weise sei es möglich, beispielsweise das Wachstum von Pollenschläuchen und die Entwicklung der Blätter gezielt zu manipulieren und so die molekularen Mechanismen pflanzlicher Wachstumsprozesse detailliert zu untersuchen. Dieser neuartige optogenetische Ansatz für die Pflanzenforschung werde in Zukunft die Analyse von bislang unverstandenen Signalwegen erheblich erleichtern, sind sich die Forscher aus Würzburg sicher.

Ein Pionier der Optogenetik

Rhodopsin ist ein von Natur aus lichtempfindliches Pigment, das die Basis der Sehkraft vieler Lebewesen bildet. Dass sich eine lichtempfindliche Ionenpumpe aus Archaebakterien (Bacteriorhodopsin) in Wirbeltierzellen einbauen lässt und dort funktioniert, hat Georg Nagel 1995 zusammen mit Ernst Bamberg am Max-Planck-Institut für Biophysik in Frankfurt erstmals nachgewiesen. 2002/2003 gelang dieser Nachweis dann auch mit lichtempfindlichen Ionenkanälen aus Algen.

Gemeinsam mit Peter Hegemann zeigte Nagel in zwei 2002 und 2003 veröffentlichten Arbeiten die Existenz von zwei lichtempfindlichen Kanalproteinen, Channelrhodopsin-1 und Channelrhodopsin- 2 (ChR1/ChR2), auf. Entscheidend war die Entdeckung, dass ChR2 eine extrem schnelle, lichtinduzierte Veränderung des Membranstroms und der Membranspannung auslöst, wenn das Gen in Wirbeltierzellen exprimiert wird. Außerdem ist ChR2 durch seine geringe Größe sehr einfach in der Anwendung.

Für diese Entdeckung wurde Nagel mittlerweile vielfach ausgezeichnet, zuletzt im Jahr 2020 – gemeinsam mit zwei weiteren Pionieren der Optogenetik – mit dem mit 1,2 Millionen US-Dollar dotierten Shaw-Preis für Biowissenschaften.

Originalpublikation

„Optogenetic control of plant growth by a microbial rhodopsin“, Yang Zhou, Meiqi Ding, Shiqiang Gao, Jing Yu-Strzelczyk, Markus Krischke, Xiaodong Duan, Jana Leide, Markus Riederer, Martin J. Mueller, Rainer Hedrich, Kai R. Konrad, Georg Nagel. Nature Plants. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-021-00860-x