Clemson, South Carolina, USA

February 9, 2021

Heat stress caused by climate change is threatening to reduce peanut crop yields and burnout this source of income and food for millions of people worldwide.

But a group of researchers led by Clemson University Plant and Environmental Sciences assistant professor Sruthi Narayanan is working to develop heat-tolerant peanut varieties they hope will help maintain peanut production and profitability. Their latest venture focuses on how lipids (fats) in peanut plant anthers are altered by heat stress.

Clemson assistant professor Sruthi Narayanan and graduate student Zolian Zoong Lwe study how heat stress affects peanuts as they work to develop heat-tolerant peanut varieties.

“Understanding these changes will aid in understanding the mechanisms of heat tolerance and help us determine how to develop heat-tolerant peanut varieties,” Narayanan said.

Peanuts are grown on about 42 million acres worldwide. They require temperatures of at least 56 degrees, with 86 degrees the optimal growing temperature. Higher temperatures can hurt yields. The Earth’s average yearly temperature has increased 2 degrees since the pre-industrial era of 1880-1900. This extra heat is driving up regional and seasonal temperatures, reducing snow cover and sea ice, intensifying heavy rainfall and changing habitat ranges for plants and animals.

Lipids provide energy for plant growth and survival. Anthers are plant male reproductive organs that produce pollen, which is transported to the stigma of the female reproductive organ in the flower, pistil, for pollination to occur and plants to reproduce.

“Reduced pollen production and viability are the major reasons for loss of peanut yields when heat stress occurs during the flowering stage,” said Zolian Zoong Lwe, a former Clemson master’s student who conducted the study under Narayanan’s guidance and is now a doctoral student at Kansas State University. “Understanding the mechanisms underlying the decrease in peanut pollen performance during heat stress will help develop tolerant peanut varieties.”

This study, funded by the National Peanut Board and the South Carolina Peanut Board and supported by the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA), began at Clemson in 2018. It involved six varieties – Bailey, Georgia 12Y, Phillips, Sugg, Tifguard and Wynne – and one breeding line, SPT06-07.

“These varieties were selected so that the study would have a range of sensitive and more heat and/or drought-tolerant cultivars,” said Dan Anco, one of the study’s researchers, as well as Clemson Extension peanut specialist and assistant professor housed at the Edisto Research and Education Center (REC) in Blackville.

Test varieties were grown in fields at the Simpson Research Farm, following field operation recommendations in the Clemson Peanut Money-Maker Production Guide. The plots received just rainwater, no irrigation. No pests nor pathogen problems were detected.

Heat tents were used to heat-stress the plants for 17 days in 2018 and 18 days in 2019. Lipids were extracted from anthers in flowers collected from the plots. Researchers found heat stress caused changes in lipids needed for the plants to reproduce. The study identified lipid metabolic traits associated with heat tolerance.

“This discovery is useful in determining lipid biomarkers (measurable/observable changes) that have important applications in breeding climate-resilient varieties,” said Sachin Rustgi, a plant breeder at the Clemson Pee Dee REC in Florence who also is part of the research team.

Other researchers involved in the study are Salman Naveed, a doctoral student at Clemson University and Ruth Welti, a biology professor at Kansas State University.

Clemson researchers Sruthi Narayanan and Zolian Zoong Lwe extract lipids to determine how lipids (fats) in peanut plant anthers are altered by heat stress.

A paper about their study appears in the Scientific Reports journal’s Dec. 17, 2020 edition of Springer-Nature.

Peanut is one of the Top 10 crops grown in South Carolina. The latest figures from the United States Department of Agriculture National Agriculture Statistics Service (USDA-NASS) show 62,000 acres of peanuts with a production value of more than $46 million harvested in the state in 2019. For 2020, the South Carolina Peanut Board reported the state had 522 peanut farmers who planted 82,000 acres and produced 278 million pounds of peanuts.

South Carolina Commissioner of Agriculture Hugh Weathers said studies such as this are important in helping promote the state’s economy.

“I’m proud that South Carolina has become one of the leading peanut-producing states and I’m committed to supporting the expansion of this industry,” Weathers said. “Peanuts are a crucial part of agribusiness’ $46 billion annual economic impact in the state.”

The Peanut Man

Peanuts are believed to have originated in South America. Information from the American Peanut Council shows commercial peanut farms could be found in the United States in the 1700s and 1800s.

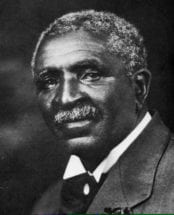

George Washington Carver

Peanuts were not extensively grown here because it was regarded as food for the poor. In addition, growing and harvesting techniques were slow and difficult. Until the Civil War, peanuts remained mainly a regional food associated with the southern states. After the war, peanut demand increased. Better equipment for production, harvesting and shelling, as well as processing, contributed to expansion of the peanut industry.

Significant advances in the peanut industry came from George Washington Carver, a man born into slavery on a Missouri farm who went on to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in agricultural sciences from what is now Iowa State University. He was a botany professor and researcher and became director of agriculture and, later, director of Research and the Experiment Station at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial School Institute, now known as Tuskegee University, in Alabama. Carver is credited with developing more than 300 products from the peanut plant, such as peanut-based ice cream, shampoo, dyes, paints, and more.

While at Tuskegee, Carver developed the Jesup Agricultural Wagon, a mule-drawn carriage outfitted with tools and necessities to help farmers. He drove the carriage out to farms to bring research-based instruction, demonstrations and supplies so that farmers could learn new ways to plant crops and use new farming tools. The USDA reports Carver reached an average of 2,000 people per month during the first summer he drove the wagon to farms.

The mule-drawn carriage George Washington Carver drove out to farms to share agricultural information with farmers was replaced by this truck in 1923.

Photo courtesy of Tuskegee University

When the Smith-Lever Act was passed in 1914 and a National Extension System was formed, the “Farmers’ College on Wheels,” as the mobile school was sometimes referred to, received additional funds to include a female home demonstration agent to ride along and bring additional information to women in the rural areas. During all visits, instructors distributed pamphlets from the Tuskegee Institute with information about farm production, nutrition, and health. In 1923 the wagon was replaced by a truck and was renamed the Booker T. Washington Agricultural School on Wheels.

Carver earned the nickname “Peanut Man” after appearing before the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee in 1921 to speak about peanuts. Soon, the whole country knew about George Washington Carver. By 1940, peanuts had become one of the Top 6 crops in the U.S.

In 1923, Carver was the first African American lecturer at Clemson University, addressing cadets in the main building chapel. Letters he wrote to a Clemson cadet can be found in the Clemson University Libraries Special Collections, located in the Strom Thurmond Building on the university’s main campus. Special Collections and Archives are currently under modified operations. For information, email archives@clemson.edu.

This study is funded by the National Peanut Board Grant No. 2012637 and South Carolina Peanut Board Grant No. 2012613. This work also is supported by the USDA-NIFA, Hatch/Multi-State Project 1013013.