Ames, Iowa, USA

June 24, 2014

By: Sarah Carlson

Midwest Cover Crop Research Coordinator

Practical Farmers of Iowa

(515) 232-5661

sarah@practicalfarmers.org

“Prevent plant” became a common phrase across the Corn Belt in 2013. Constant rainfall and cool temperatures early on kept farmers from planting corn and then soybeans. The spring of 2014 has been better, but some prevent plant acres have already been determined.

Many Iowa, Minnesota and northern Illinois farmers got their first chance to try cover crop radishes last year on those prevent plant acres. Because corn and soybeans usually cover ag land until early October there is little time to get solid growth from a cover crop radish. But last year, with lands idle and open, come mid-July many farmers decided to jump in and plant radishes. Radishes, farmers say, reduce soil compaction due to the large taproot the plant grows. Also well-known are the benefits to the soil “livestock”: the microbes, worms, fungi and more in the soil providing nutrient cycling for the cash crops. Those farmers planting radishes for many years on their farms share that they have seen improvements in water infiltration and overall soil health. One benefit of radishes that may become more evident soon is weed control for the year following radishes.

A 2012 article in “Agronomy Journal” from author Yvonne Lawley at the University of Manitoba investigated the nature of the cover crop radish’s weed control. Since a cover crop radish does not overwinter and only a “carcass” is left the following spring, its weed control potential seems hard to believe. Lawley, along with Dr. John Teasdale from USDA-ARS in Beltsville and Dr. Ray Weil from the University of Maryland, studied this question: What mechanism of weed suppression does a forage radish cover crop employ?

Four experiments were conducted to determine if the forage radish cover crop method of weed suppression was through plant chemicals, allelopathy, or direct competition with weeds in the fall. Since radishes winterkill in the Corn Belt and eastern U.S., they are only physically present and growing during the fall. In one experiment, at the end of August in 2005, 2006 and 2007, radishes were drilled at a rate of 12.5 pounds per acre. Radishes were either left to grow and intact in the plot or radish biomass in various combinations was removed in November near the time of a hard frost.

Of the cover crop combinations tested, radish taproots and shoots were removed in one treatment; in another treatment, only radish shoots were removed but taproots were left in place; and in a final treatment, double the amount of radish shoots and taproots were piled onto an existing radish stand. Where no radishes were planted in the fall, radish shoots and taproots were added to plots in the spring. Another treatment included plots only receiving the radish shoots. Finally, two control plots had no cover crops and were either weedy checks or weed-free checks that were hand-weeded.

Lawley hypothesized that if the weed suppression mechanism was plant chemicals, then intact radishes or spring-applied radish biomass would suppress weeds as the radishes decomposed. There would be no weed suppression on the plots where radishes were removed in the fall. But if the weed control mechanism was due to direct competition during fall growth, there would be no weed suppression in the plots where no radish was seeded in the fall but biomass was applied in the spring.

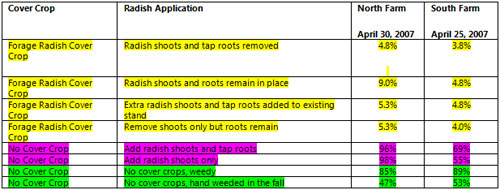

The following spring, the best weed suppression was observed in the plots where radishes had been grown and either kept intact or had different parts of biomass removed in November (yellow highlighted area). Weed suppression lasted until mid-spring. The no-radish plots that were amended with radish biomass in the spring (pink highlighted area) had weed coverage similar to the weedy no-radish check plots (green highlighted area). (Table 1) The results suggest that weed suppression by radishes is due to direct competition in the fall, not plant chemicals.

Table 1. Data snapshot of mean percent weed coverage among cover crop and radish treatments in 2007 at USDA-ARS Beltsville, MD North and South Farms.

Soil health improvements and weed control are important factors to farmers growing crops, but would farmers modify their farming systems in the “colder” Midwestern Corn Belt to be able to add cover crop radish? Cover Crop Champion Steve McGrew, from southwest Iowa, has tried radish on his farm, but says “I haven’t had a solid stand of radish to see its benefits.” Steve expresses a common concern among corn and soybean farmers in more northern climates.

“I might use radish as a species in a mix,” Steve says, “but I see radish fitting best as a summer cover crop.”

Cover crop radish needs to be planted early – sometime around early August – for sufficient growth. Some farmers are flying on cover crops into standing corn or soybean fields, but with normal planting populations few farmers have had success with this method. Another option is to tweak current practices. A cover crop farmer from southern Iowa, Seth Watkins, says he’s had luck with radishes: “We’ve flown on radishes and turnips into standing corn, but our corn population is near 25,000 to 28,000 instead of the higher 36,000 plants per acre.” Seth farms some poorer ground and finds that for highest corn yields, planting at a lower population is best. That decision has proved to be even smarter because he can now grow cover crop radishes, which he feels boost his soil health faster. He hasn’t focused on using radishes to control weeds, but this is something that might be of interest.

Cover crop radish can be an important addition to a cover cropping mixture. Its multi-tasking characteristics provide not only improved nutrient cycling and soil characteristics, but now research shows its growth in the fall physically controls weeds well through mid-spring. That may be just enough reason to tweak our system and try it on your farm.

REFERENCE:

Lawley, Yvonne E., John R. Teasdale and Ray R. Weil. 2012.

The Mechanism for Weed Suppression by a Forage Radish Cover Crop

Agronomy Journal 104(2):205-214.

Abstract

Little is known about the mechanism of winter annual weed suppression by forage radish (Raphanus sativus L. variety longipinnatus) winter cover crops. Previous studies suggest that allelopathy from decomposing residue and competition due to rapid canopy development contribute to weed suppression by other Brassica cover crops. Four contrasting experimental approaches were used to identify the mechanism of weed suppression by forage radish cover crops. Results of a field based cover crop residue-transfer experiment supported the hypothesis that fall cover crop weed competition is the dominant mechanism of weed suppression following forage radish cover crops. A high level of early spring weed suppression was observed where forage radish grew in the fall regardless of whether residues were left in place or removed. In contrast, there was limited weed suppression in bare soil treatments that received additions of forage radish tissues. Bioassays using cover crop amended soil or aqueous extracts of cover crop tissues and amended soil did not reveal any allelopathic activity limiting seed germination or seedling establishment. In a field-based weed seed bioassay, forage radish cover crops did not inhibit emergence of winter-planted weed seeds relative to a no cover crop control. Forage radish amended soils stimulated seedling growth of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) in all types of bioassays. The results of the four experiments in this study point to a common conclusion that fall weed competition is the dominant mechanism for early spring weed suppression following forage radish winter cover crops.