Zurich, Switzerland

June 3, 2020

Soya and clover have their very own fertiliser factories in their roots, where bacteria manufacture ammonium, which is crucial for plant growth. Although this has long been common knowledge, scientists have only recently described the mechanism in detail. With biotechnology, this knowledge could now help make agriculture more sustainable.

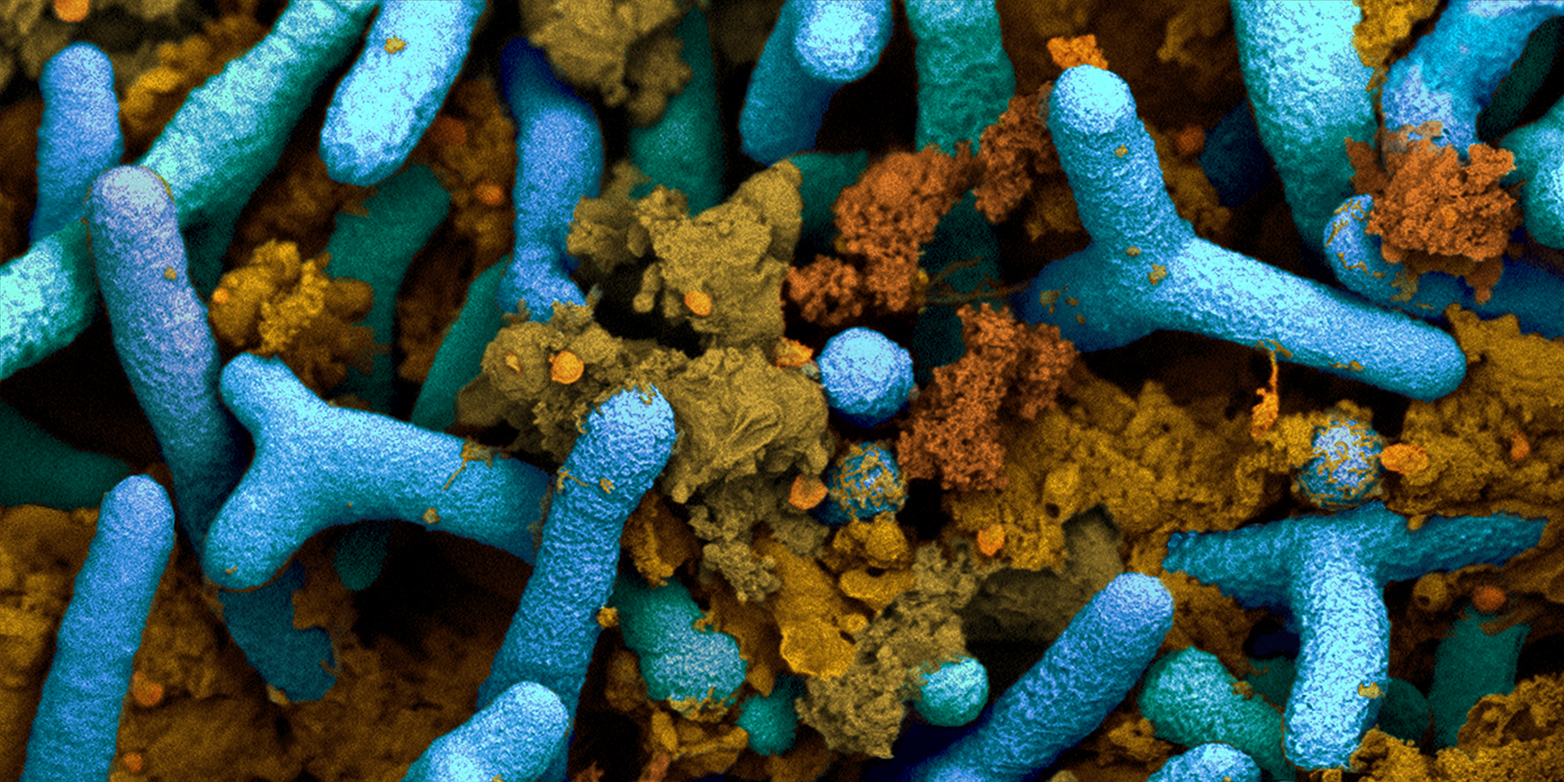

Rhizobia (in blue) in the roots of a plant. The brown structures are plant proteins (coloured electron microscope image). (Photograph: ETH Zurich / Anne-Greet Bittermann)

Plants need nitrogen in the form of ammonium if they are to grow. In the case of a great many cultivated plants, farmers are obliged to spread this ammonium on their fields as fertiliser. Manufacturing ammonium is an energy-intensive and costly process – and today’s production methods also release large amounts of CO2.

However, a handful of crops replenish their own supply of ammonium. The roots of beans, peas, clover and other legumes harbour bacteria (rhizobia) that can convert nitrogen from the air into ammonium. This symbiosis benefits both the plants and the rhizobia in an interaction that scientists had until now seen as relatively straightforward: the bacteria supply the plant with ammonium; in return, the plant provides them with carbonaceous carboxylic acid molecules.

A surprisingly complex interaction

Under the leadership of Beat Christen, Professor of Experimental Systems Biology, and Matthias Christen, a scientist at the Institute for Molecular Systems Biology, ETH researchers have now succeeded in demonstrating that the plant-bacteria interaction is in fact surprisingly complex. Along with carbon, the plant gives the bacteria the nitrogen-rich amino acid arginine.

“Although nitrogen fixation in rhizobia has been studied for many years, there were still gaps in our knowledge,” Beat Christen says. “Our new findings will make it possible to reduce farmers’ dependence on ammonium fertiliser, thereby making agriculture more sustainable.”

Using systems biology methods, the researchers investigated and unravelled the metabolic pathways of rhizobia that cohabit with clover and soya. Joining forces with ETH Professor Uwe Sauer, they verified the results in growth experiments with plants and the bacteria in the lab. The scientists suspect that their new findings will apply not just to clover and soya, and that the metabolic pathways of other legumes are regulated in similar fashion.

A battle royal, not a voluntary symbiosis

The findings shed new light on the coexistence of plants and rhizobia. “This symbiosis is often misrepresented as a voluntary give and take. In fact, the two partners do their utmost to exploit each other,” Matthias Christen says.

As the scientists were able to demonstrate, soya and clover do not exactly roll out the red carpet for their rhizobia, but rather regard them as pathogens. The plants try to cut off the bacteria’s oxygen supply and expose them to acidic conditions. Meanwhile, the bacteria toil ceaselessly to survive in this hostile environment. They use the arginine present in the plants because it enables them to switch to a metabolism that does not require much oxygen.

To neutralise the acidic environment, the microbes transfer acidifying protons to nitrogen molecules taken from the air. This produces ammonium, which they get rid of by conducting it out of the bacterial cell and passing it on to the plant. “The ammonium that is so crucial for the plant is thus merely a waste product in the bacteria’s struggle for survival,” Beat Christen says.

Converting molecular nitrogen into ammonium is an energy-intensive process not only for industry but also for rhizobia. The newly characterised mechanism explains why the bacteria expend so much energy on the process: it ensures their survival.

Paving the way to sustainable agriculture

Agriculture and biotechnology will be able to use this new insight to transfer the process of bacterial nitrogen fixation to non-leguminous crops, such as wheat, maize or rice. Scientists have made many attempts to achieve this transfer, but have always met with limited success because an important piece of the metabolic puzzle was missing. “Now that we’ve mapped the mechanism down to the last detail, this is likely to improve our chances of achieving a favourable result,” Beat Christen says.

One possible approach is to use biotechnological methods to insert all genes necessary for the metabolic pathway directly into the crops. Another line of action would be to transfer these genes into bacteria interacting with the roots of wheat or maize. These bacteria do not currently convert nitrogen in the air to ammonium, but biotechnology has the means to make it happen – and the ETH researchers will now pursue this approach.

Reference

Flores-Tinoco CE, Tschan F, Fuhrer T, Margot C, Sauer U, Christen M, Christen B: Co-catabolism of arginine and succinate drives symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Molecular Systems Biology, 3 June 2020, doi: 10.15252/msb.20199419

Related article

First bacterial genome created entirely with a computer (ETH News 01.04.2019)

Wie Bakterien Soja düngen

Soja und Klee haben in ihren Wurzeln eigene Düngerfabriken – Bakterien stellen dort das für die Pflanzen wichtige Ammonium her. Obschon dies schon seit Langem bekannt ist, haben Wissenschaftler den Wirkungsmechanismus erst jetzt im Detail beschrieben. Das könnte nun helfen, mit Biotechnologie die Landwirtschaft nachhaltiger zu gestalten.

Pflanzen benötigen Stickstoff in Form von Ammonium, um wachsen zu können. Bei sehr vielen Kulturpflanzen müssen Landwirte dieses Ammonium als Dünger aufs Feld führen. Dessen Herstellung ist energieintensiv und teuer, und bei der heutigen Produktionsweise wird viel CO2 freigesetzt.

Einige wenige Ackerpflanzen besorgen sich den Ammoniumnachschub allerdings selbst: In den Wurzeln von Bohnen, Erbsen, Klee und anderen Hülsenfrüchtlern leben Bakterien, welche den Stickstoff aus der Luft in Ammonium umwandeln können. Die Pflanzen und die sogenannten Knöllchenbakterien profitieren beide, und bisher war die wissenschaftliche Sicht auf diese Symbiose recht simpel: Die Pflanze bezieht von den Bakterien Ammonium, und die Bakterien erhalten im Gegenzug von der Pflanze kohlenstoffreiche Karbonsäuremoleküle.

Komplexeres Zusammenspiel als angenommen

ETH-Forschende unter der Leitung von Beat Christen, Professor für experimentelle Systembiologie, und Matthias Christen, Wissenschaftler am Institut für molekulare Systembiologie, konnten nun zeigen, dass das Zusammenspiel von Pflanze und Bakterien komplexer ist: Die Bakterien beziehen von der Pflanze neben dem Kohlenstoff auch die stickstoffreiche Aminosäure Arginin.

«Obschon die Stickstofffixierung der Knöllchenbakterien seit vielen Jahrzehnten untersucht wird, war das Wissen unvollständig», sagt Beat Christen. «Unsere neuen Erkenntnisse werden es ermöglichen, die Abhängigkeit der Landwirtschaft vom Ammoniumdünger zu verringern und damit die Landwirtschaft nachhaltiger zu gestalten.»

Die Forschenden untersuchten und entschlüsselten die Stoffwechselwege von Knöllchenbakterien, die mit Klee und Soja zusammenleben, mit Methoden der Systembiologie. Zusammen mit ETH-Professor Uwe Sauer überprüften sie die Ergebnisse in Wachstumsexperimenten von Pflanzen und den Bakterien im Labor. Die Wissenschaftler vermuten, dass die neuen Erkenntnisse nicht nur für Klee und Soja gelten, sondern dass die Stoffwechselwege bei den anderen Hülsenfrüchtlern ähnlich ablaufen.

Eher ein Kampf als Freiwilligkeit

Die Erkenntnisse liefern eine neue Sicht auf die Koexistenz von Pflanzen und Knöllchenbakterien. «Anders als häufig dargestellt, ist diese Symbiose nicht geprägt von einem freiwilligen Geben und Nehmen. Vielmehr nutzen sich die beiden Partner aus, wo es nur geht», sagt Matthias Christen.

Wie die Wissenschaftler zeigen konnten, legen Soja und Klee ihren Knöllchenbakterien nicht den roten Teppich aus, sondern empfangen sie wie einen Krankheitserreger: Die Pflanzen versuchen den Bakterien den Sauerstoff abzudrehen und setzen sie einem sauren Umfeld aus. Die Bakterien rackern sich ab, um in diesem unwirtlichen Milieu zu überleben. Sie nutzen das Arginin der Pflanzen, weil sie dank diesem auf einen Stoffwechsel umstellen können, für den sie nur wenig Sauerstoff benötigen.

Um die saure Umgebung zu neutralisieren, übertragen die Mikroben sauermachende Protonen auf Stickstoffmoleküle aus der Luft. Dadurch entsteht Ammonium, welches sie sich vom Hals schaffen, indem sie es aus der Bakterienzelle schleusen und somit an die Pflanze geben. «Das für die Pflanze so wertvolle Ammonium ist für die Bakterien also bloss ein Abfallprodukt aus ihrem Überlebenskampf», sagt Beat Christen.

Die Umwandlung von molekularem Stickstoff in Ammonium ist nicht nur für die Industrie energieintensiv, sondern auch für die Knöllchenbakterien. Der neu beschriebene Mechanismus erklärt, warum die Bakterien so viel Energie aufwenden: Er ermöglicht ihnen zu überleben.

Mit Biotechnologie zu nachhaltiger Landwirtschaft

Das neue Wissen wird man in der Landwirtschaft und in der Biotechnologie nutzen können, um die bakterielle Stickstofffixierung auf Kulturpflanzen, die keine Hülsenfrüchtler sind, zu übertragen, also zum Beispiel auf Weizen, Mais oder Reis. Wissenschaftler haben das zwar schon mehrfach versucht – weil ein wichtiges Puzzleteil des Stoffwechsels bisher nicht bekannt war allerdings nur mit bescheidenem Erfolg. «Jetzt, wo wir den Mechanismus im Detail entschlüsselt haben, dürften die Chancen steigen, diesen Ansatz zu einem erfolgreichen Ende zu führen», sagt Beat Christen.

Es ist denkbar, alle für den Stoffwechselweg nötigen Gene mit biotechnologischen Verfahren direkt in die Kulturpflanzen einzufügen. Ein anderer Ansatz wäre, diese Gene in Bakterien zu übertragen, die mit den Wurzeln von Weizen oder Mais wechselwirken. Diese Bakterien wandeln derzeit keinen Stickstoff aus der Luft in Ammonium um; biotechnologisch könnte man ihnen dazu verhelfen. Diesen Ansatz werden auch die ETH-Forschenden nun weiterverfolgen.

Literaturhinweis

Flores-Tinoco CE, Tschan F, Fuhrer T, Margot C, Sauer U, Christen M, Christen B: Co-catabolism of arginine and succinate drives symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Molecular Systems Biology, 3. Juni 2020, doi: 10.15252/msb.20199419

Verwandte Artikel